No Ordinary Terrain

(2021)

collective show with Sandra Zaffarese, Aaron Bezzina, Keit Bonnici At MUŻA, supported by MUŻA and the Arts Council Malta

collective show with Sandra Zaffarese, Aaron Bezzina, Keit Bonnici At MUŻA, supported by MUŻA and the Arts Council Malta

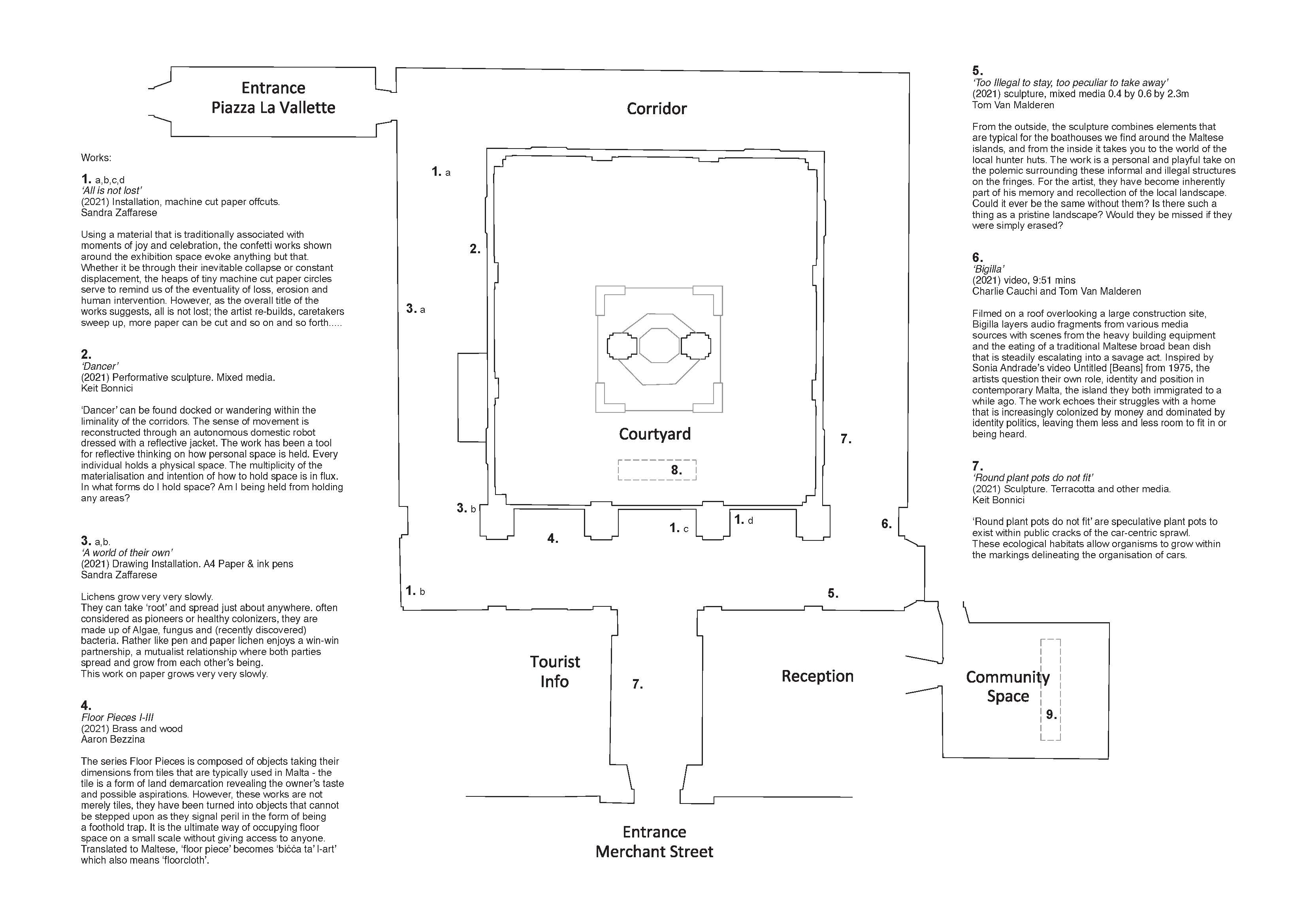

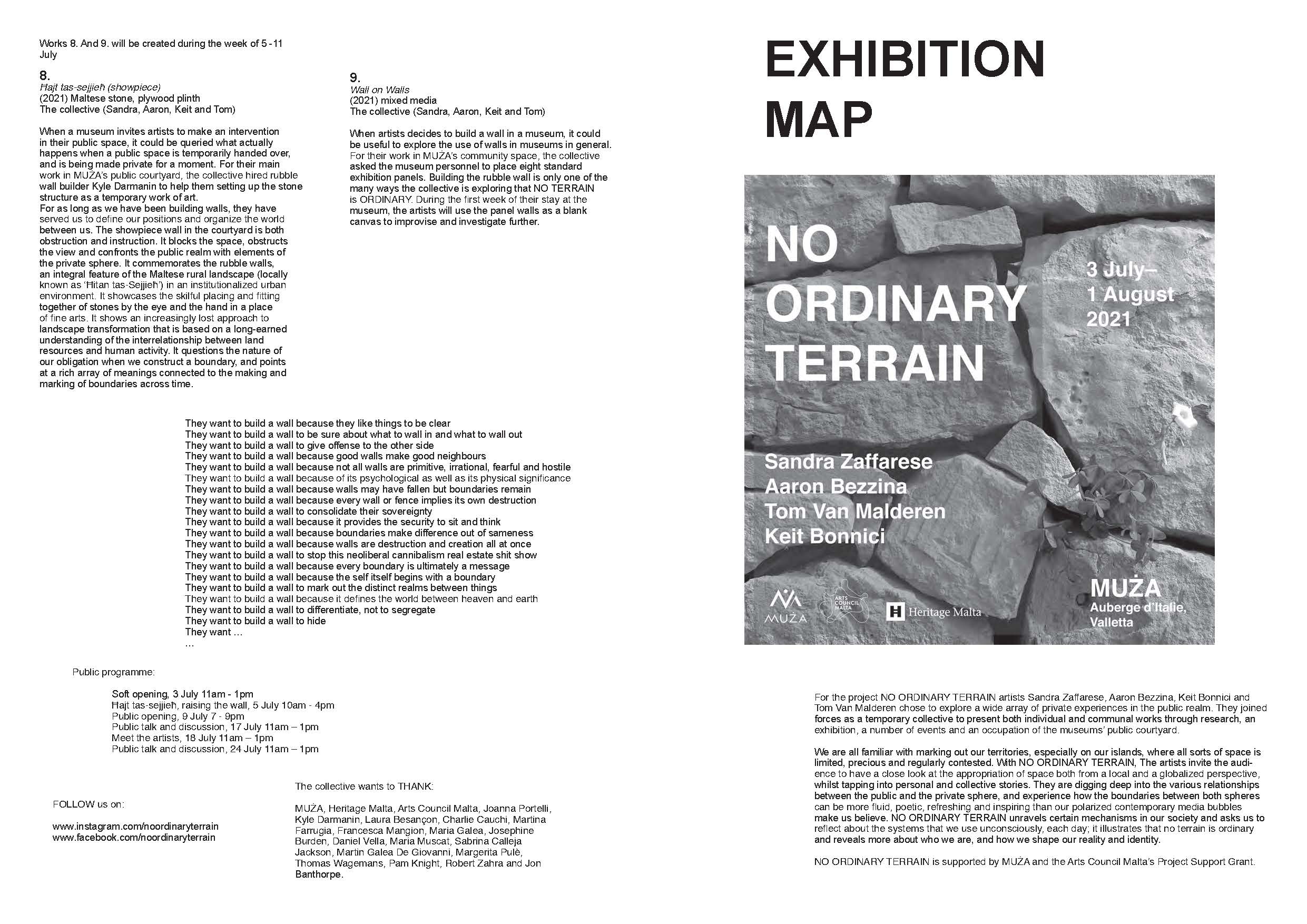

For the project NO ORDINARY TERRAIN artists Sandra Zaffarese, Aaron Bezzina, Keit Bonnici and Tom Van Malderen chose to explore a wide array of private experiences in the public realm. They joined forces as a temporary collective to present both individual and communal works through research, an exhibition, a number of events and an occupation of the museums’ public courtyard.

We are all familiar with marking out our territories, especially on our islands, where all sorts of space is limited, precious and regularly contested. With NO ORDINARY TERRAIN, The artists invite the audience to have a close look at the appropriation of space both from a local and a globalized perspective, whilst tapping into personal and collective stories. They are digging deep into the various relationships between the public and the private sphere, and experience how the boundaries between both spheres can be more fluid, poetic, refreshing and inspiring than our polarized contemporary media bubbles make us believe. NO ORDINARY TERRAIN unravels certain mechanisms in our society and asks us to reflect about the systems that we use unconsciously, each day; it illustrates that no terrain is ordinary and reveals more about who we are, and how we shape our reality and identity.

(Text: Francesca Mangion)

In Mojave thinking, body and land are the same. The words are separated only by the letters ‘ii and ‘a: ‘iimat for body, ‘amat for land. In conversation, we often use a shortened form for each: mat-. Unless you know the context of a conversation, you might not know if we are speaking about our body or our land. You might not know which has been injured, which is remembering, which is alive, which was dreamed, which needs care. You might not know we mean both. (Natalie Diaz, Postcolonial Love Poem)

LAND

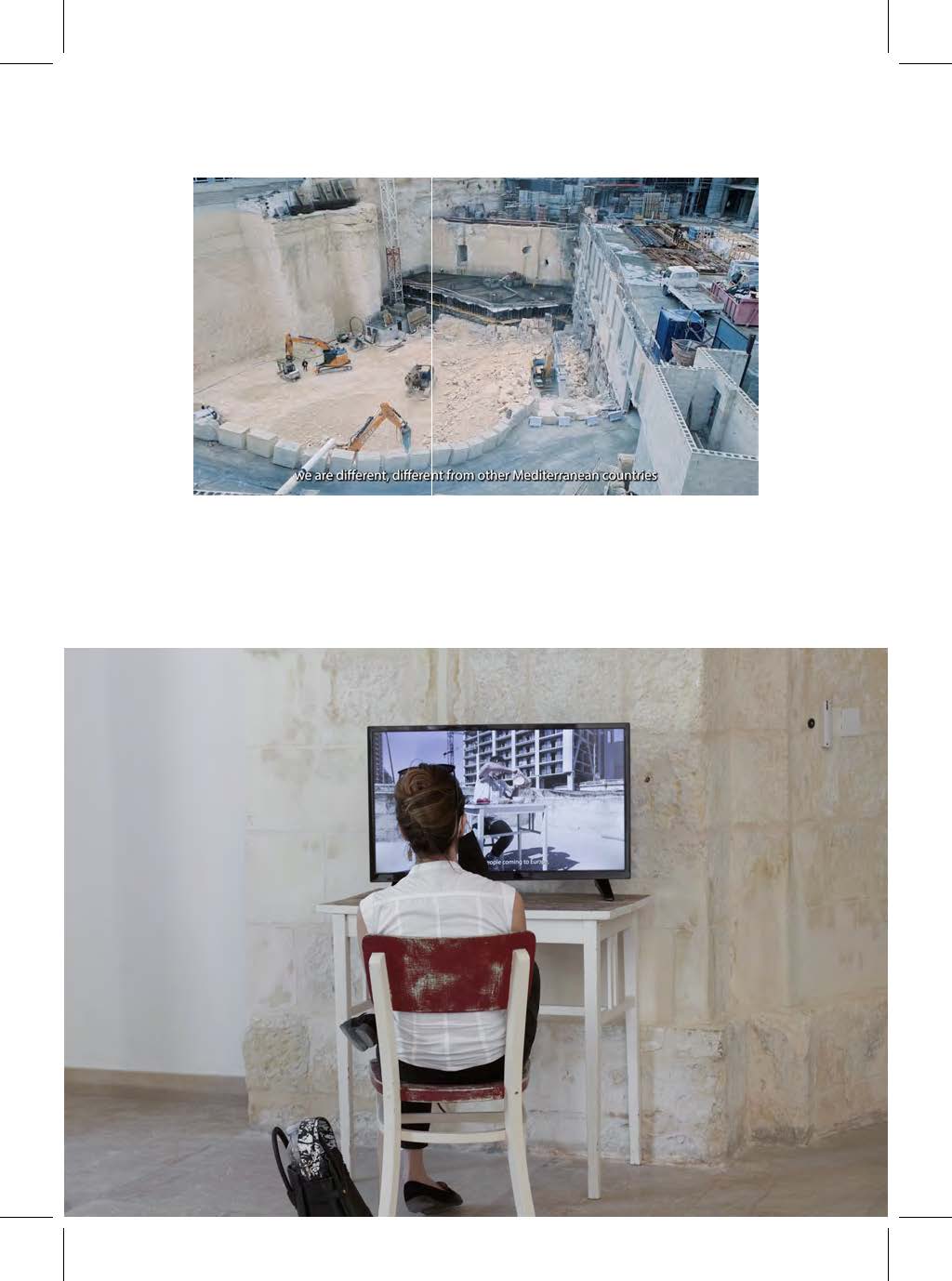

A discourse about land is inevitably punctuated by questions on borders, illegalities, appropriation, freedom of movement and territorial pegs. Despite the justified tribulations, No Ordinary Terrain lends a voice to multiple positions on the subject; from the sharply delineated opinions which have contributed greatly to a polarised landscape and shifting to softer, more nuanced views that are more conducive to an appropriate critical analysis.

Land and art might share the same word in Maltese, yet, the two worlds do not converge as often as one might expect. No Ordinary Terrain - a research project constituted of a number of events and an exhibition at MUŻA- starts off as an exploration of the physical manifestations of territory and its thresholds. Its scope is quickly widened to also absorb the textual, political and conceptual manifestations. The exhibition is made up of a plurality of these thresholds, intertwining and enmeshing them into one overarching narrative that makes up No Ordinary Terrain. Territorial thresholds might be the most primitive and easily recognisable markers of ownership but other important thresholds are also to be found in museums; between the curator and the inviting institution; the artist and the viewer; between a work and another.

BODIES

Noticeably, No Ordinary Terrain is missing a curator. The decision to forego one certainly injects more agency and follows the streak of soft positions and explorations that the collective proposes. These positions can be read as playful provocations that nonetheless aim at breaking open certain limitations and function as safeguards, ensuring that institutions hold on to the promise of keeping the museum a fundamental site of the democratic sphere. Undeniably, museums keep wielding considerable power, yet, they are also places where the attitudes, beliefs and values that govern our social relations are shaped, so it is necessary that they remain sites where freedom of expression reigns.

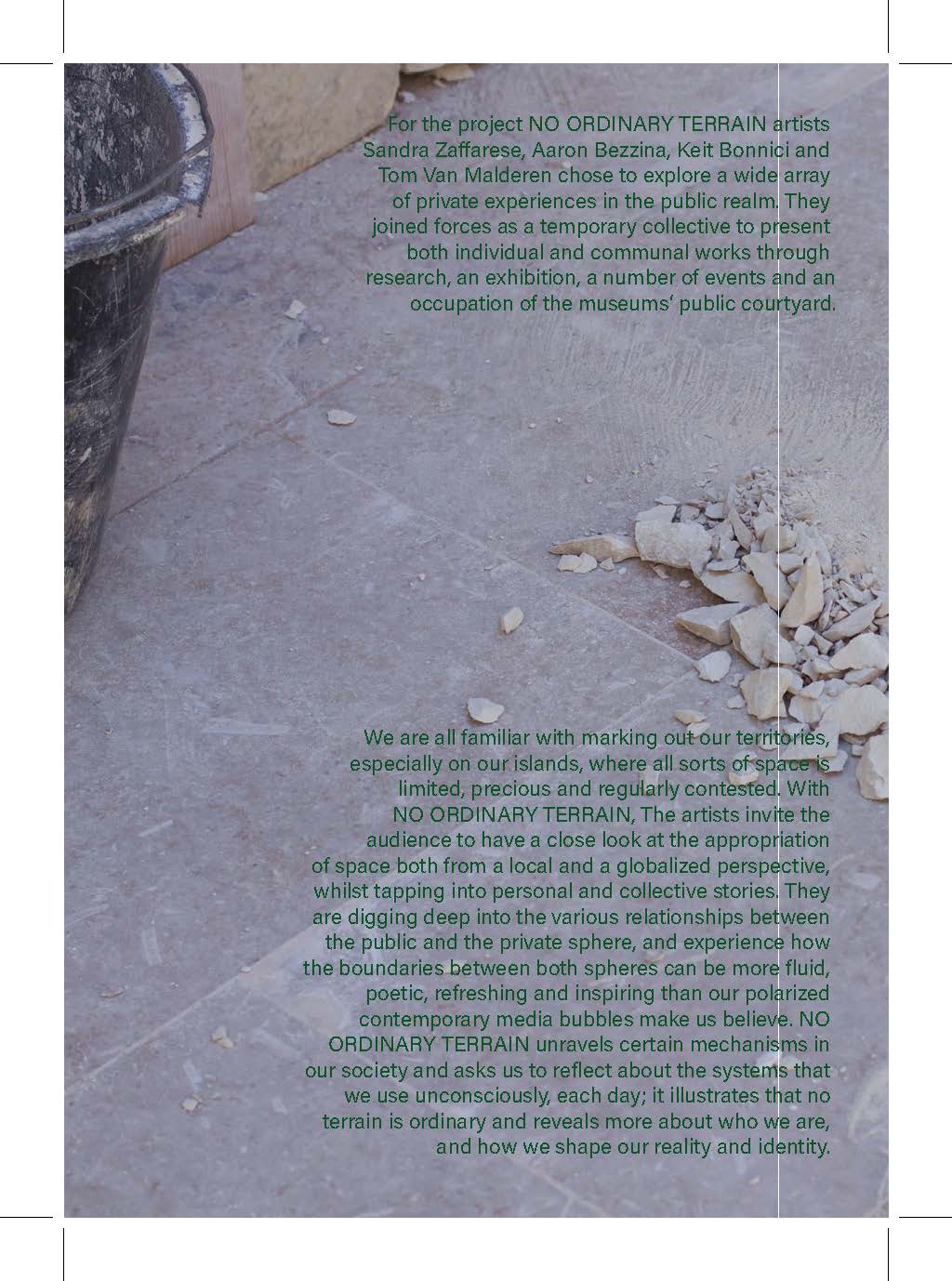

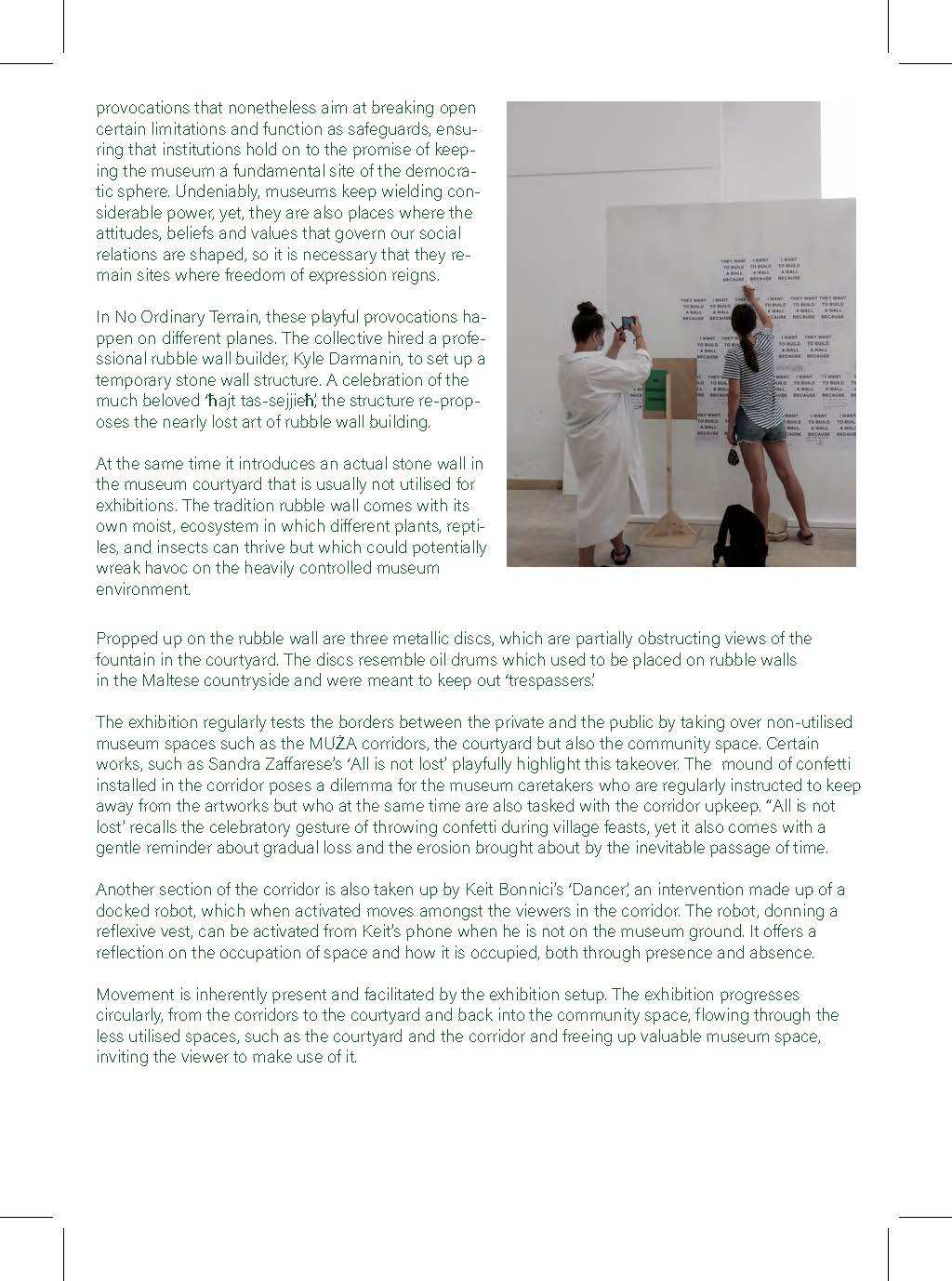

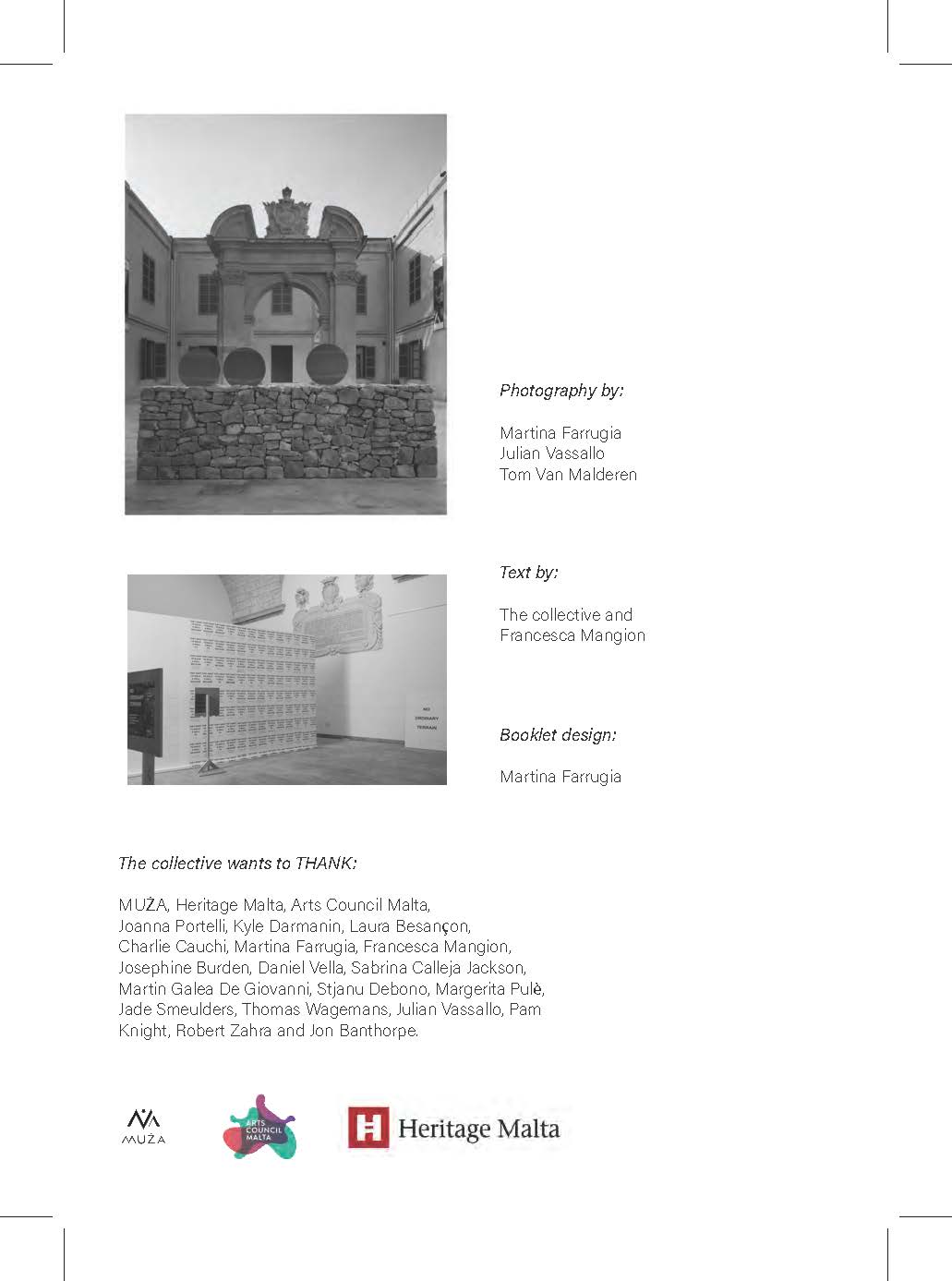

In No Ordinary Terrain, these playful provocations happen on different planes. The collective hired a professional rubble wall builder, Kyle Darmanin, to set up a temporary stone wall structure. A celebration of the much beloved ‘ħajt tas-sejjieħ’, the structure re-proposes the nearly lost art of rubble wall building. At the same time it introduces an actual stone wall in the museum courtyard that is usually not utilised for exhibitions. The tradition rubble wall comes with its own moist, ecosystem in which different plants, reptiles, and insects can thrive but which could potentially wreak havoc on the heavily controlled museum environment.

Propped up on the rubble wall are three metallic discs, which are partially obstructing views of the fountain in the courtyard. The discs resemble oil drums which used to be placed on rubble walls in the Maltese countryside and were meant to keep out ‘trespassers’.

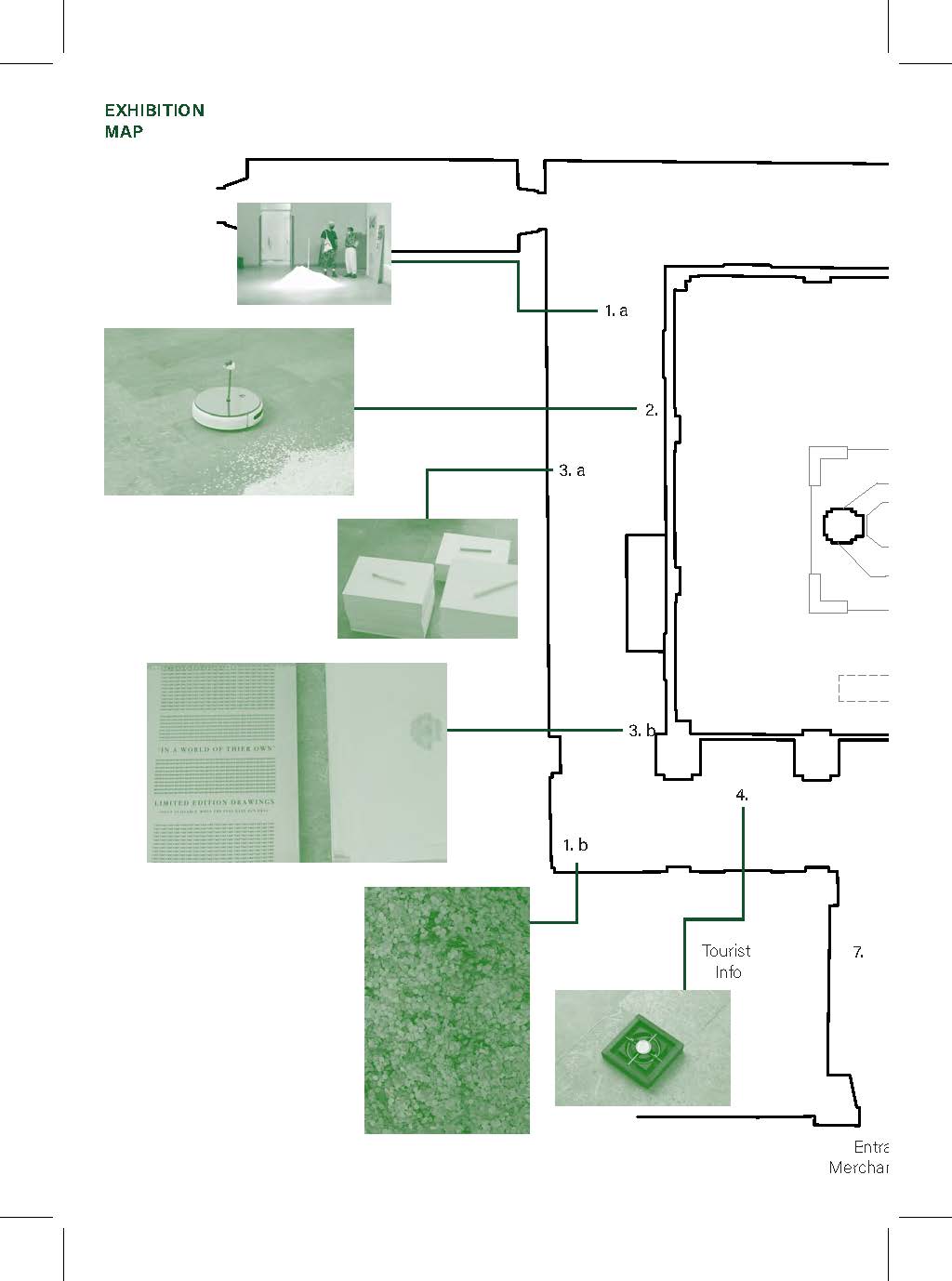

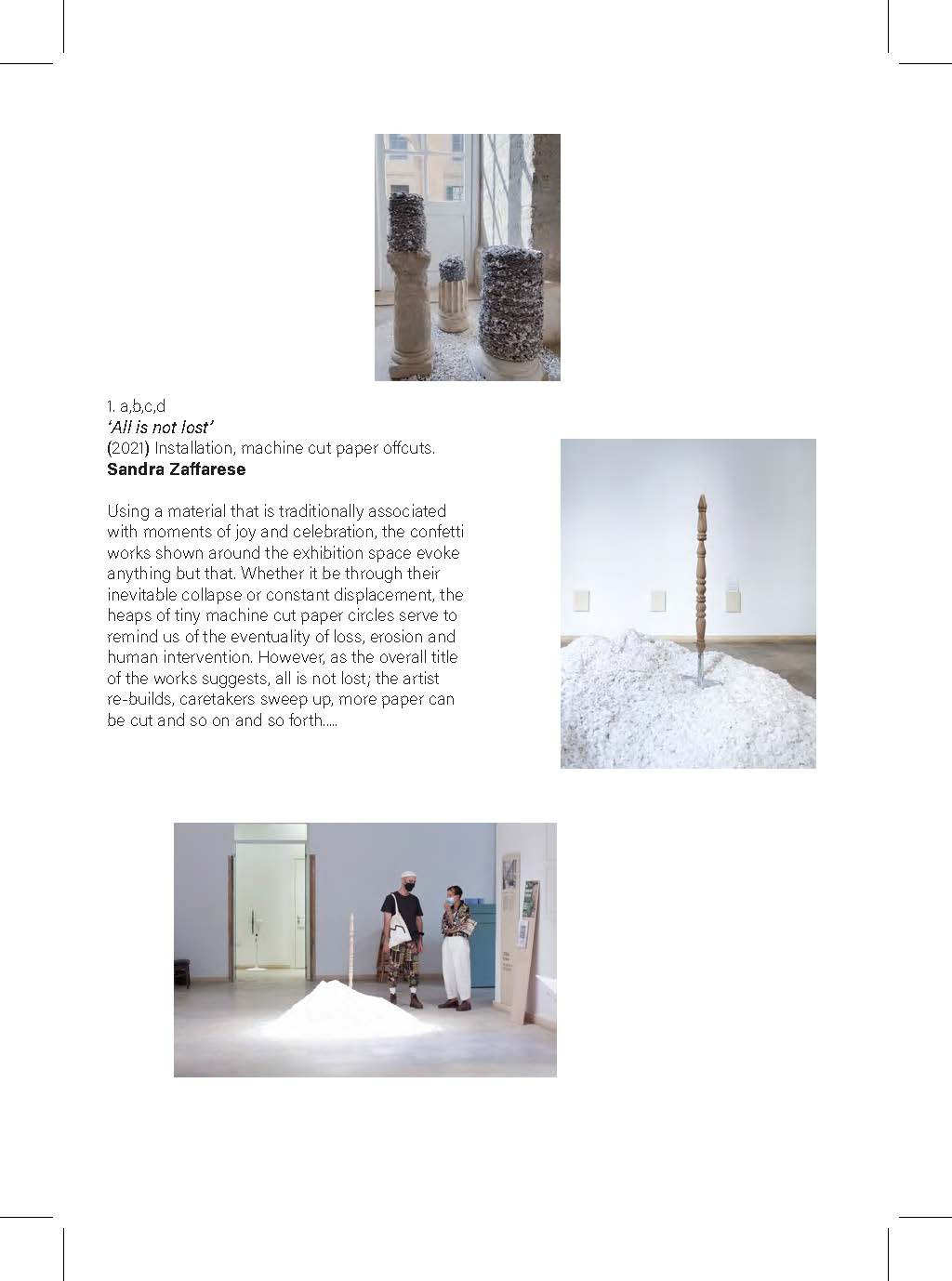

The exhibition regularly tests the borders between the private and the public by taking over non-utilised museum spaces such as the MUŻA corridors, the courtyard but also the community space. Certain works, such as Sandra Zaffarese’s ‘All is not lost’ playfully highlight this takeover. The mound of confetti installed in the corridor poses a dilemma for the museum caretakers who are regularly instructed to keep away from the artworks but who at the same time are also tasked with the corridor upkeep. “All is not lost’ recalls the celebratory gesture of throwing confetti during village feasts, yet it also comes with a gentle reminder about gradual loss and the erosion brought about by the inevitable passage of time.

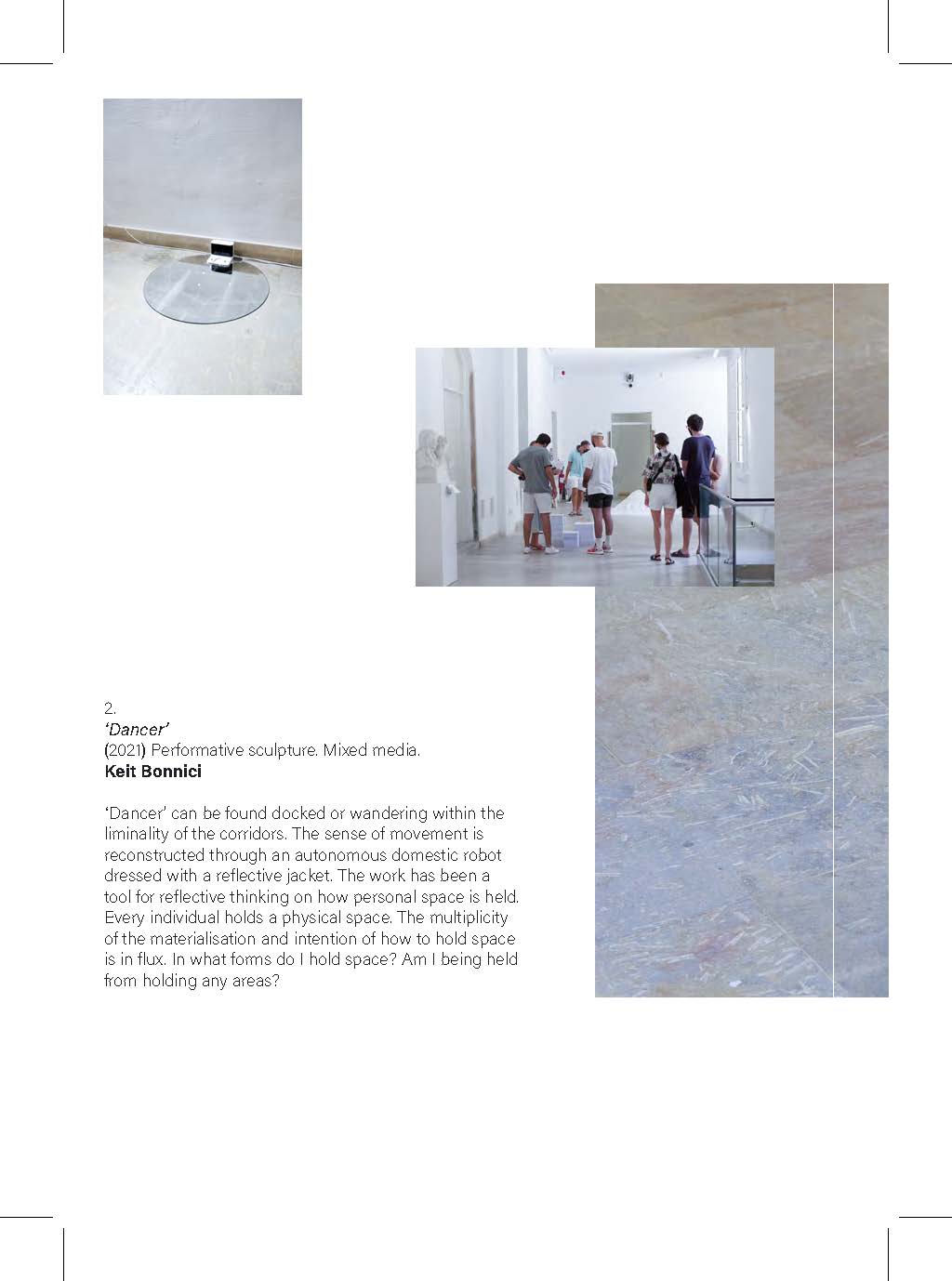

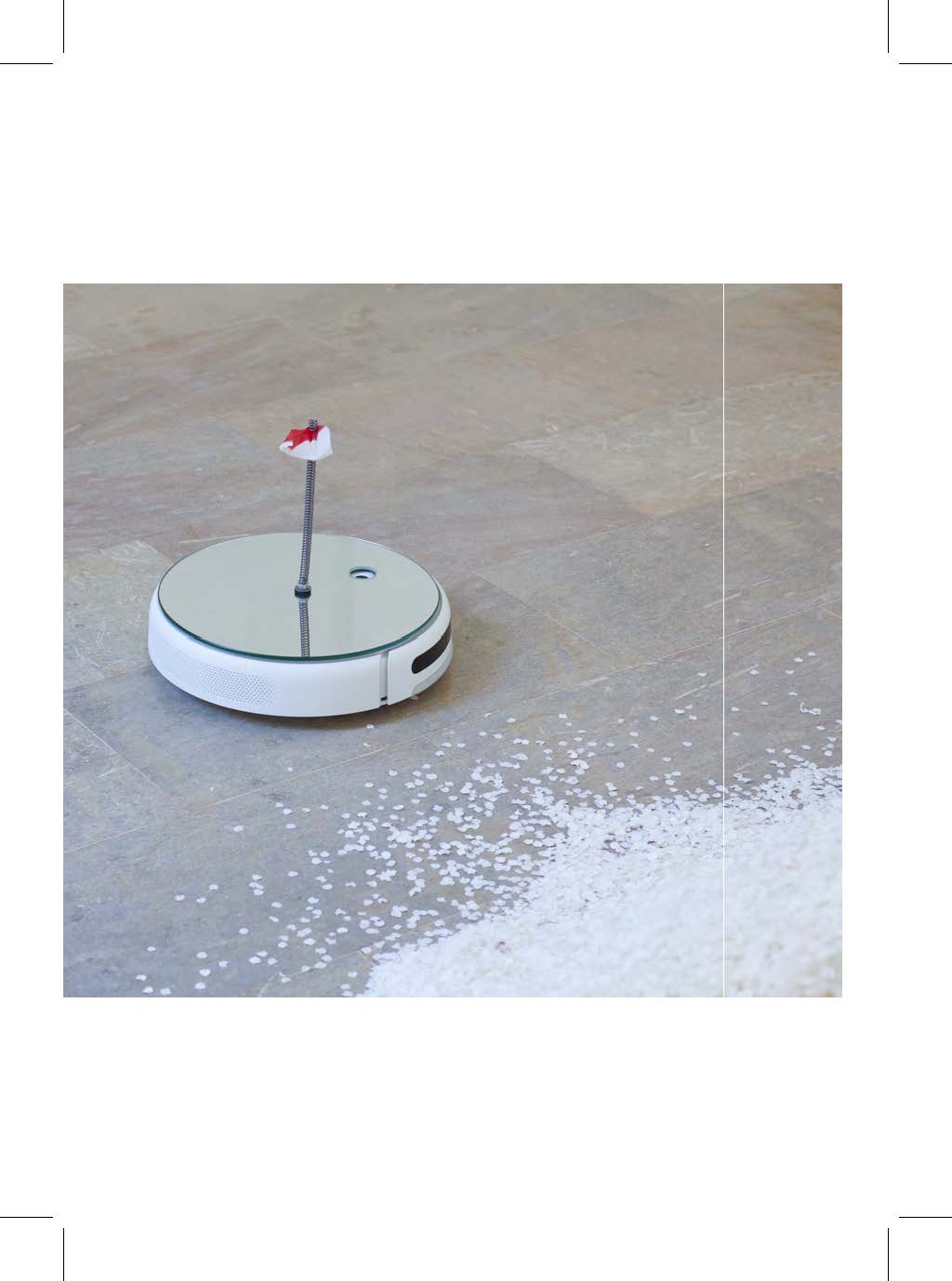

Another section of the corridor is also taken up by Keit Bonnici’s ‘Dancer’,an intervention made up of a docked robot, which when activated moves amongst the viewers in the corridor. The robot, donning a reflexive vest, can be activated from Keit’s phone when he is not on the museum ground. It offers a reflection on the occupation of space and how it is occupied, both through presence and absence.

Movement is inherently present and facilitated by the exhibition setup. The exhibition progresses circularly, from the corridors to the courtyard and back into the community space, flowing through the less utilised spaces, such as the courtyard and the corridor and freeing up valuable museum space, inviting the viewer to make use of it.

![]()

NOT BEING ON THE FENCE BUT SITTING ON ONE

The title, No Ordinary Terrain seems to be a veiled invitation. It instils in the viewer a desire to look at this familiar terrain and also be able to grasp its non-ordinary features. So there is an invitation to look differently at the things around us or, rather to look more closely at our surroundings. Looking becomes an active act - one that requires presence and purpose. Through a renewed way of looking, surroundings which tend to become transparent in their prevalence, can become perceptible again. Comparably, seemingly closed, polarised positions can finally start to be unpacked.

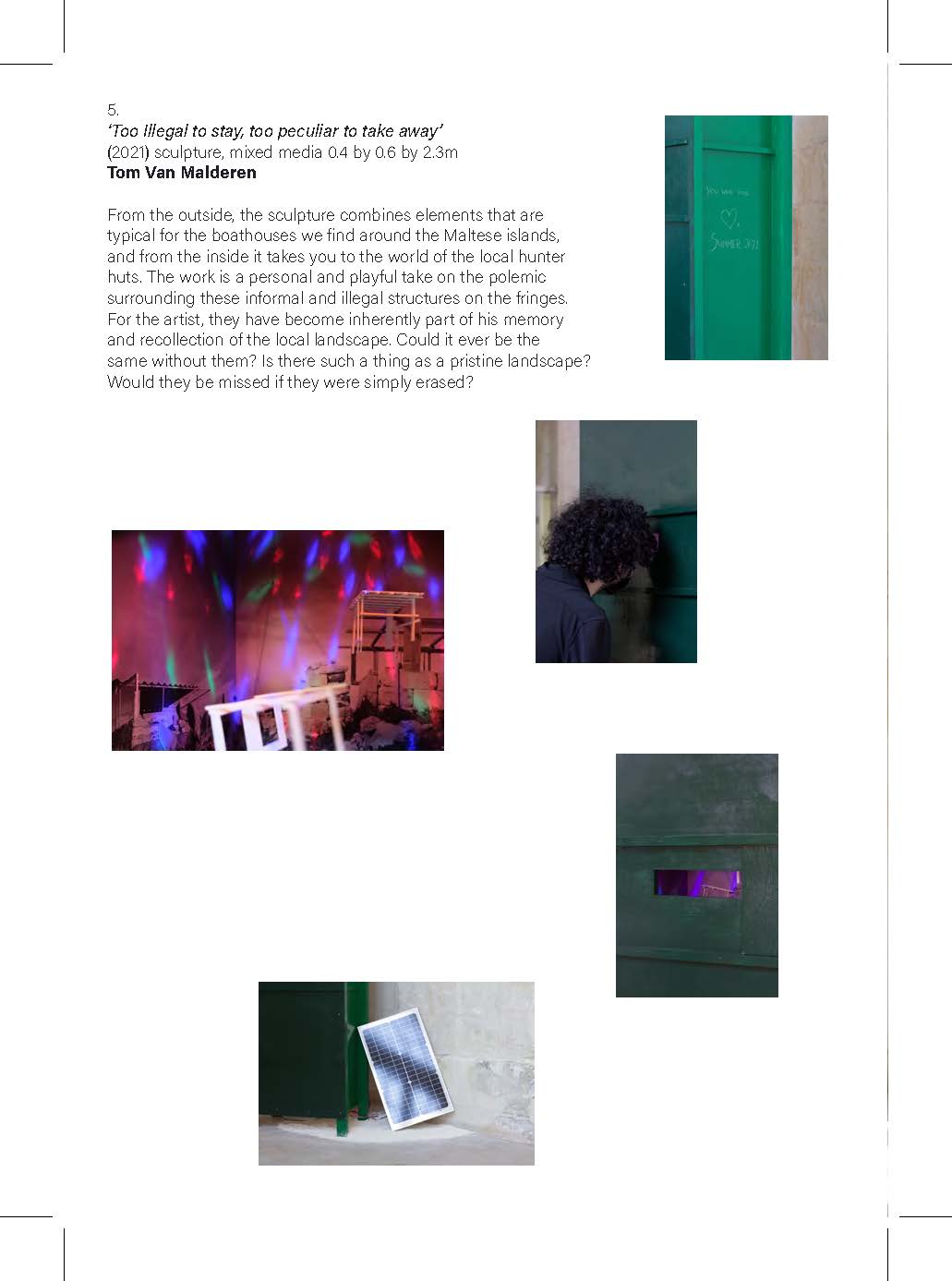

Tom Van Malderen’s ‘Too Illegal to stay, too peculiar to take away’, sits somewhere on this territory. ‘Too Illegal to stay, too peculiar to take away’ is a sculpture that combines elements borrowed from Maltese boathouses and others from traditional local hunting huts. Boathouses and hunting huts share certain characteristics; both possess aesthetically dubious features and are in blatant breach of the law. Yet, one cannot deny that they still form part of the local landscape and the illegality of an act doesn’t mean that they cannot enter our collective consciousness.

Our understanding of ourselves in relation to the other, especially when we are dealing with national identity is determined by a process that we are all participating in. Edward Said speaks of the cultural archive, a collective store that retains sayings, stories but also other types of knowledge that we make use of and that can be used as a measure of our existence in the world. This repository is internalised by the very same people who construct it but it is then externalised through policies, laws, or popular culture.

![]()

ROOT(ED)LESSNESS?

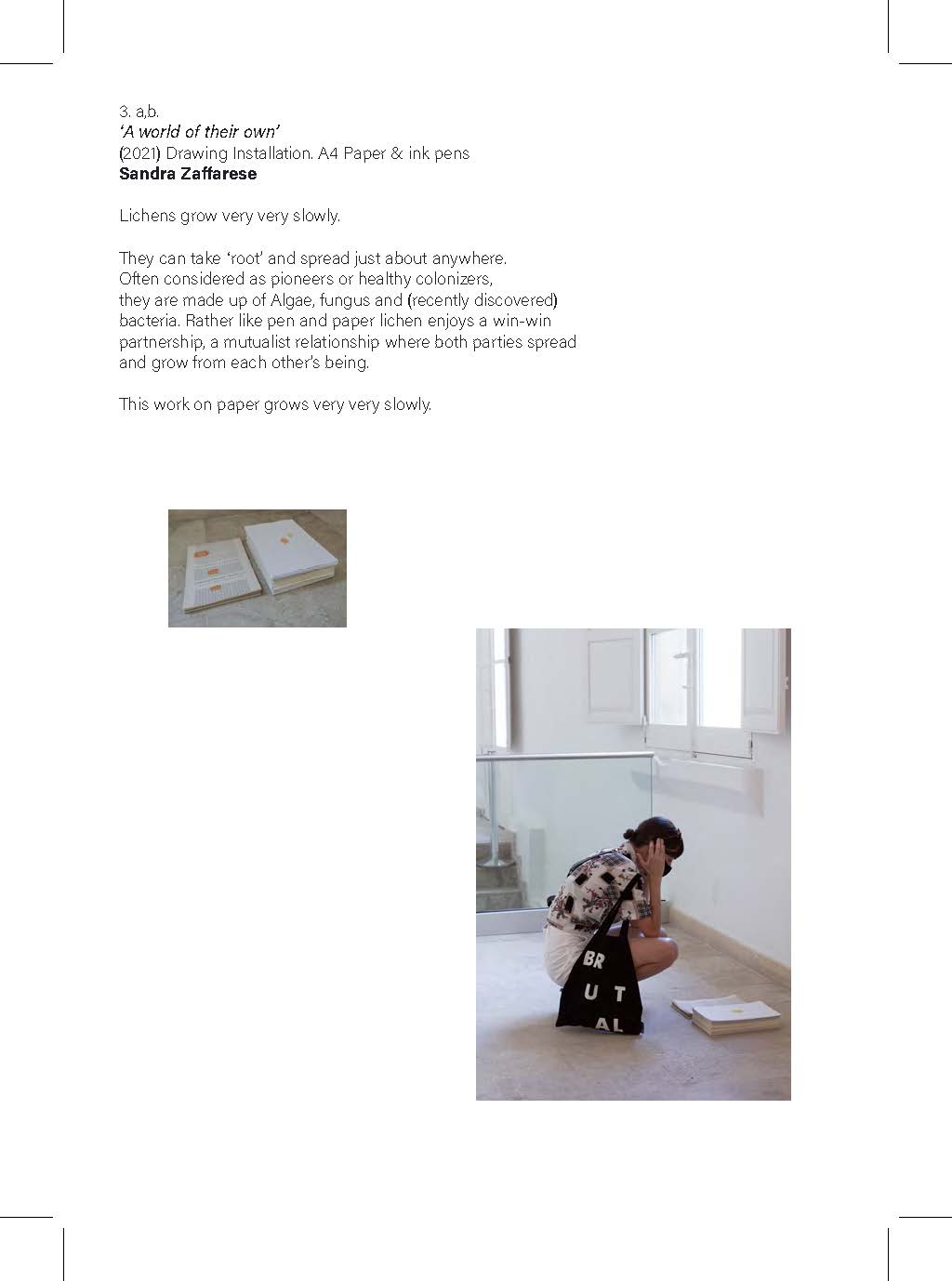

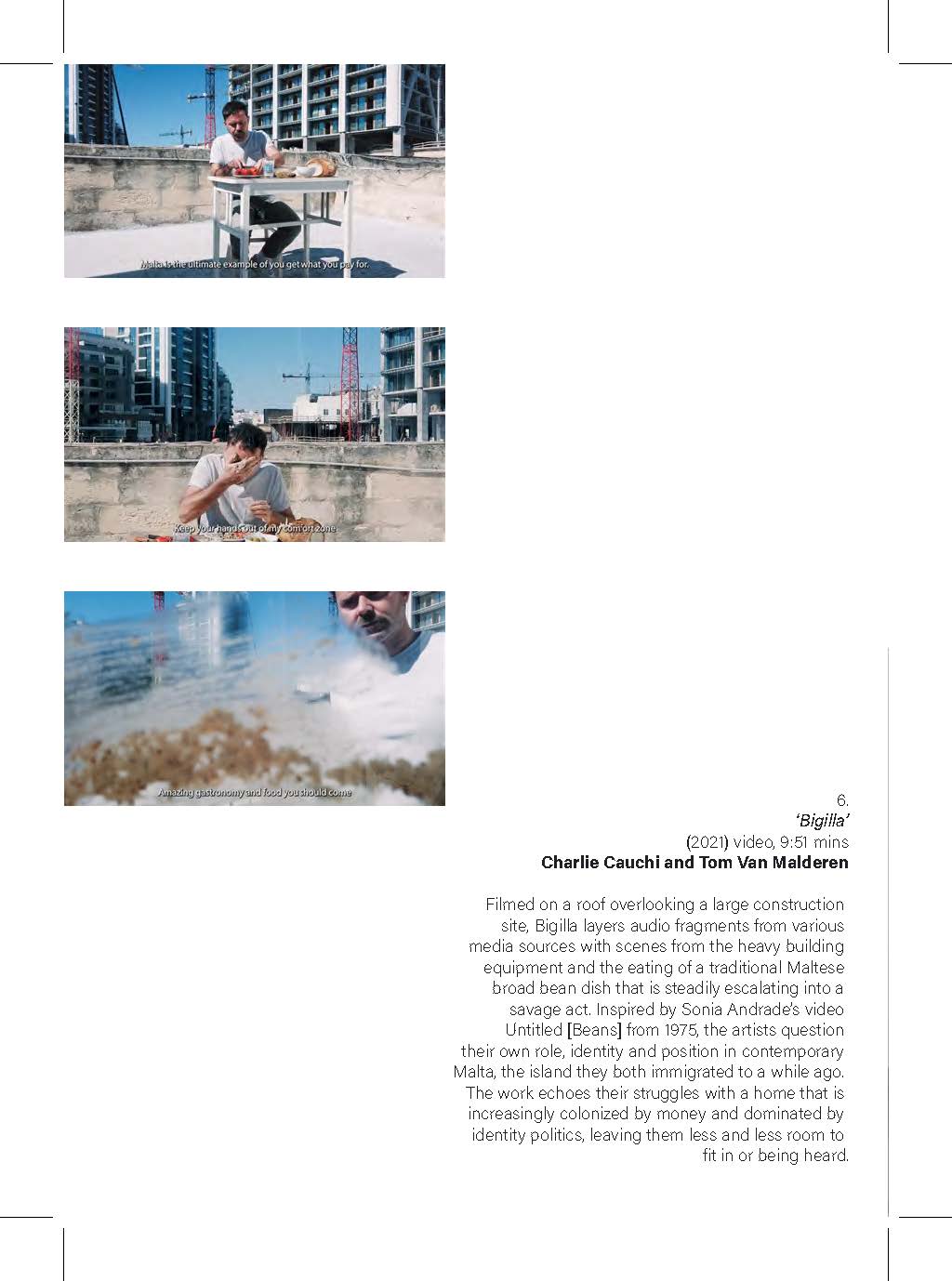

How entrenched is this repository in our lives? Charlie Cauchi and Tom Van Malderen’s ‘Bigilla’ is a work that questions both artists’ identity and roots in Malta, the island they both immigrated to some years ago. It is a work that questions the artists’ place in country increasingly riddled by rampant racism. Sandra Zaffarese’s ‘A world of their own’ is a delicate drawing installation made up of only paper and ink. The work changes over time, growing and rooting like a lichen infestation. Lichens are healthy colonisers, so just like pen and paper they share a ‘mutualist relationship’. Roots come up again in Keit Bonnici’s ‘Round plant pots do not fit’. It plays with the notion of roots, creating a work that speculates on the existence of plants which, despite unfavourable circumstances, thrive, finding their way through cracks amidst the urban sprawl. The artist presents us an instance where rooting down has a favourable outcome, yet the notion of being rooted, of setting down roots, is often commensurate with situations leading to territorial issues and aggression. Édouard Glissant’s rhizomatic practice in his Poetics of Relations favours an enmeshed root system with no predatory rootstock taking over permanently.

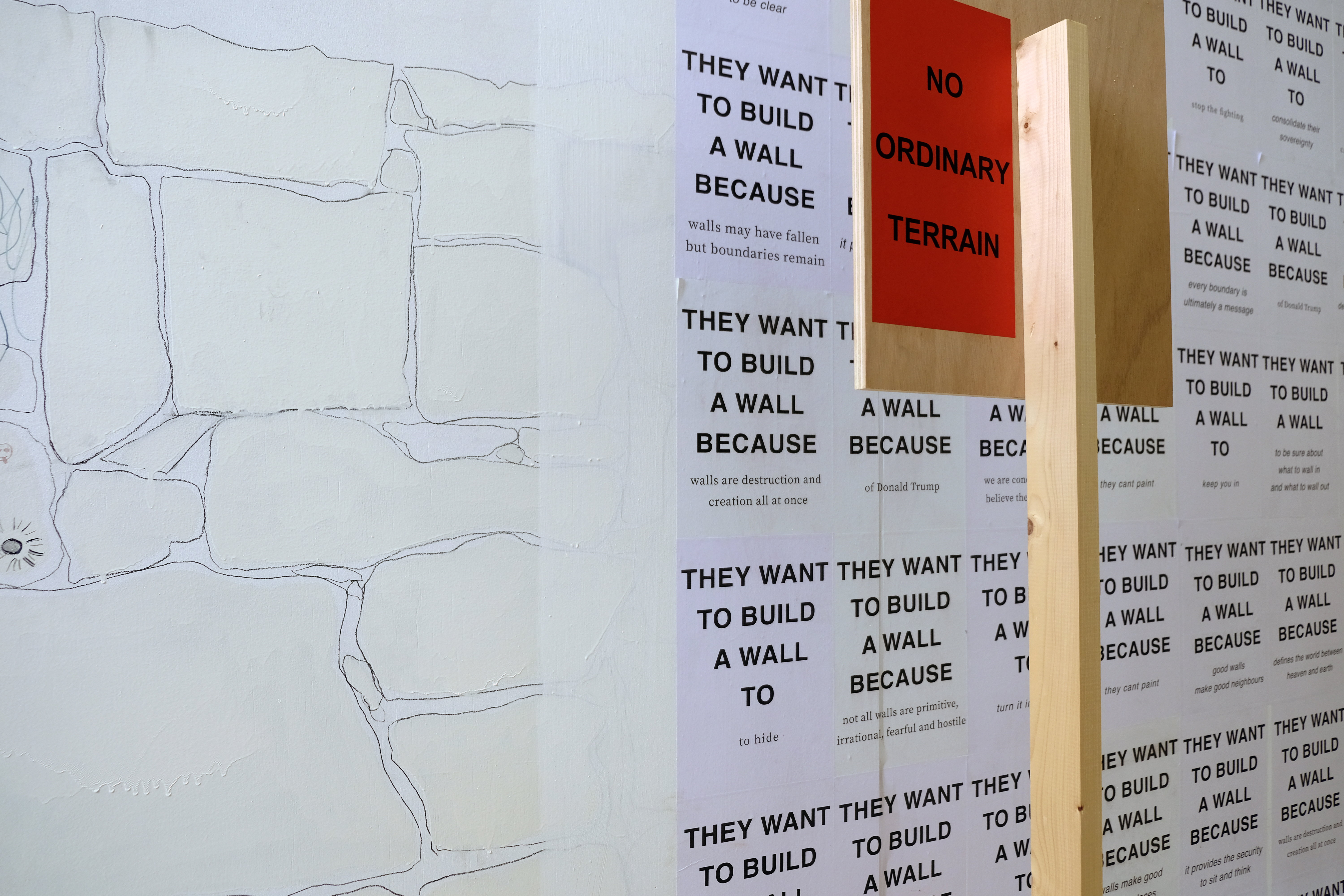

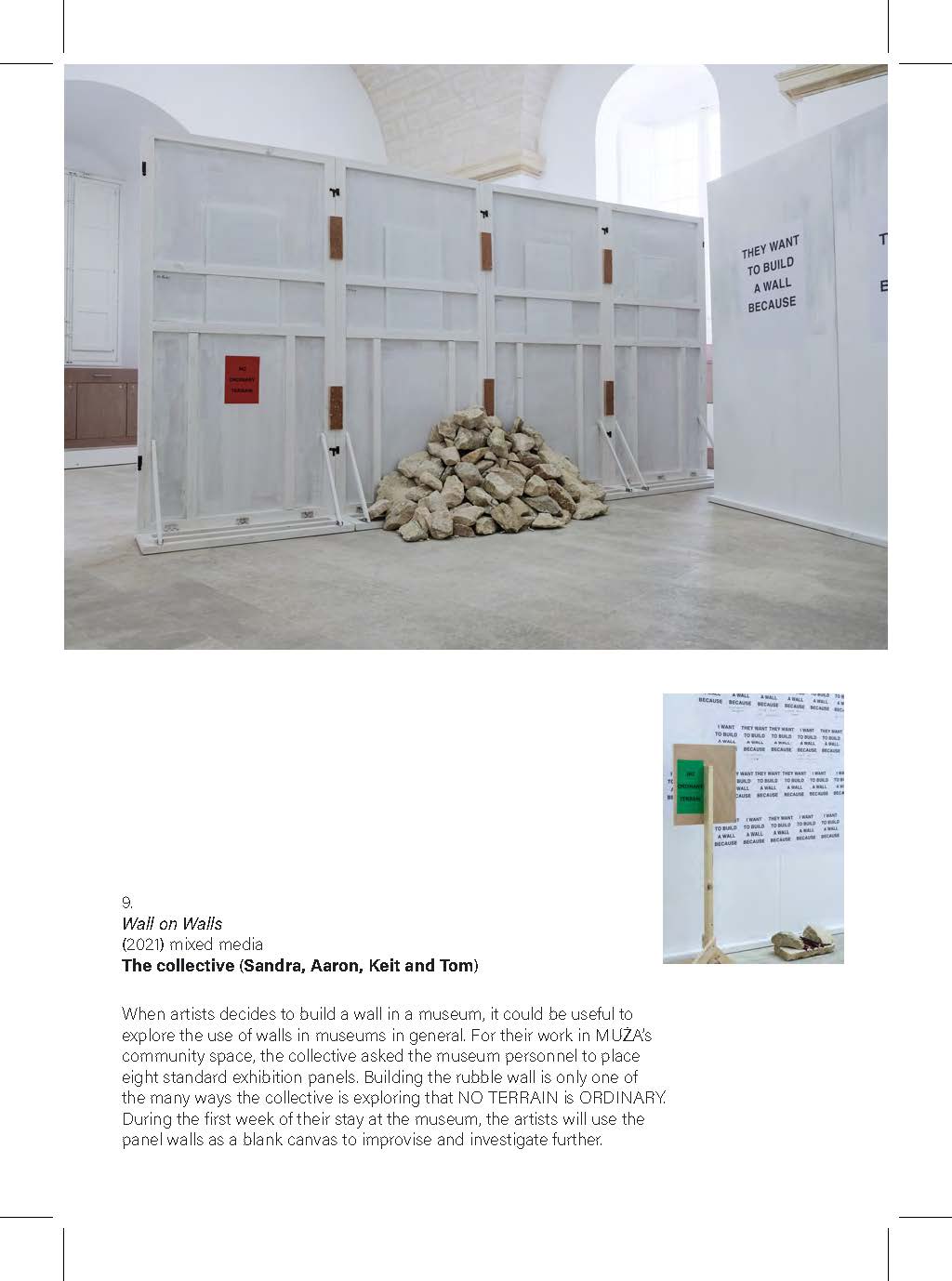

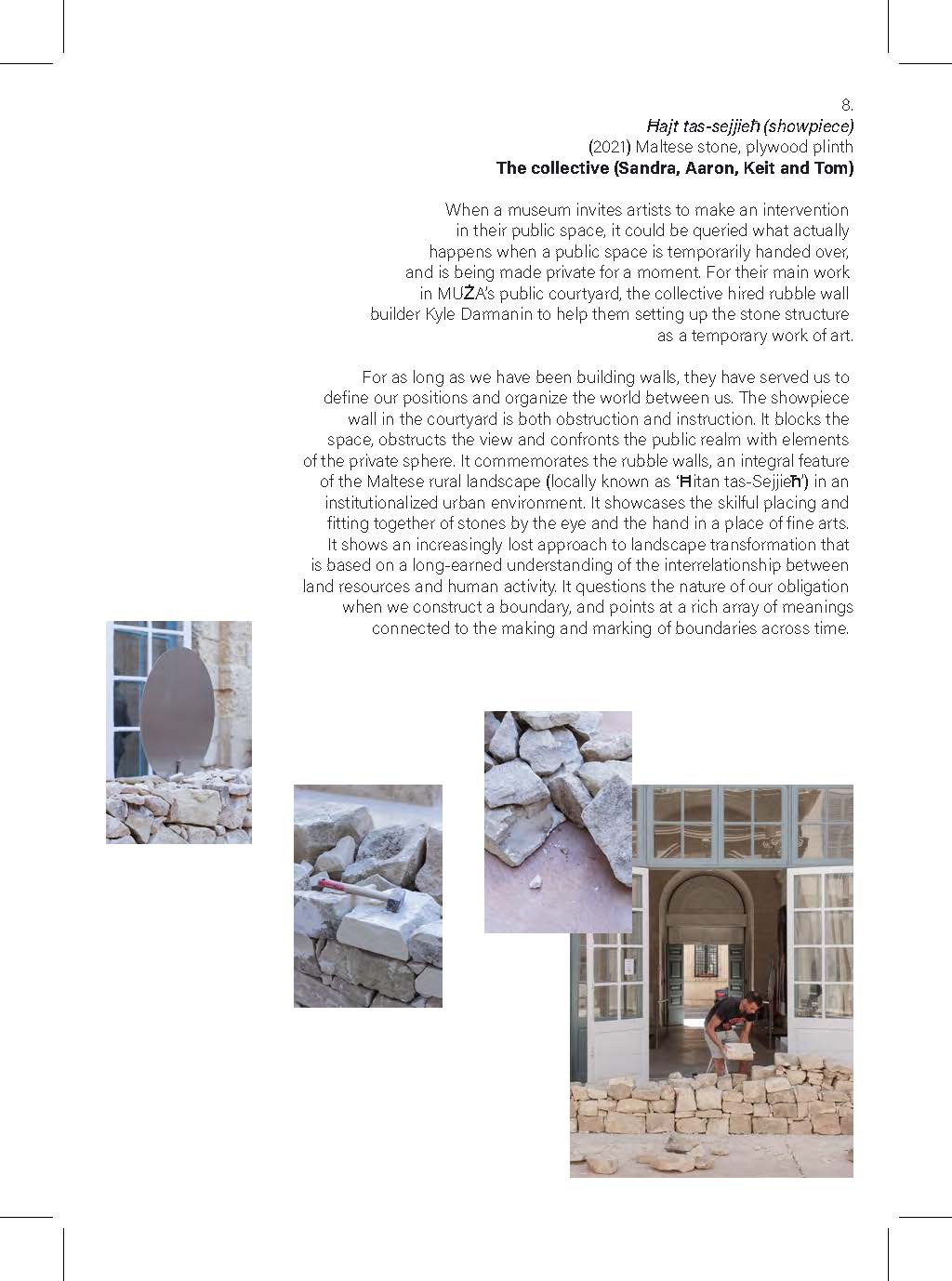

Installed in the community space, one encounters 'Wall on Walls’, where the viewers are invited to express and leave their own personal reflections about walls. These expressions take the form of brief textual statements. The outcomes differ but a rather high percentage express concern at the increasing presence of walls in our lives and at how they are being used as powerful segregational tools aimed at impacting our freedom of movement.

![]()

DO GOOD FENCES REALLY MAKE GOOD NEIGHBOURS?

Seared into our mind we have the image of Alan Kurdi, the Kurdish-Syrian boy who passed away on September 2, 2015 during his family’s voyage from Syria, where their Kurdish-majority city had been taken over by ISIL. The photo, quickly becoming a symbol of a geopolitical moment was picked up by major news outlets around the world becoming a point of reflection on a series of grave failures that had ultimately led to the tragedy.

“Freedom of movement” describes the right of a person to travel within a country, or to leave that country and later return to it. It was adopted by the United Nations in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and can be applied to those who are jailed within their own nation or who seek to travel abroad, whether as a refugee, immigrant, or tourist. The term rose to prominence during the recent refugee crisis, when the world first became subsumed by a seemingly endless flow of stories about migration. Every day, we learned about the journeys undertaken by refugees and the nations that welcomed them, or those who sought to stem their influx.

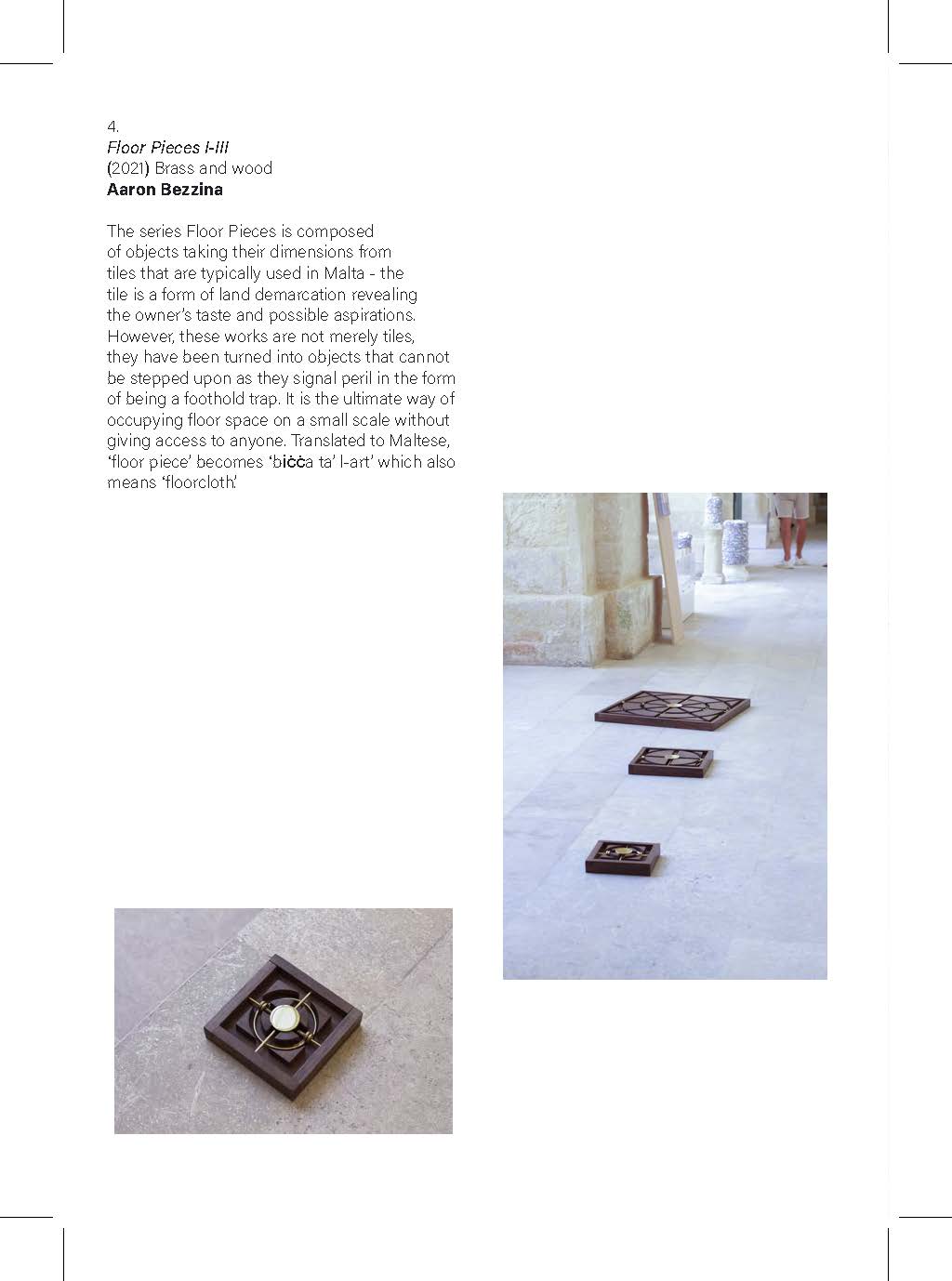

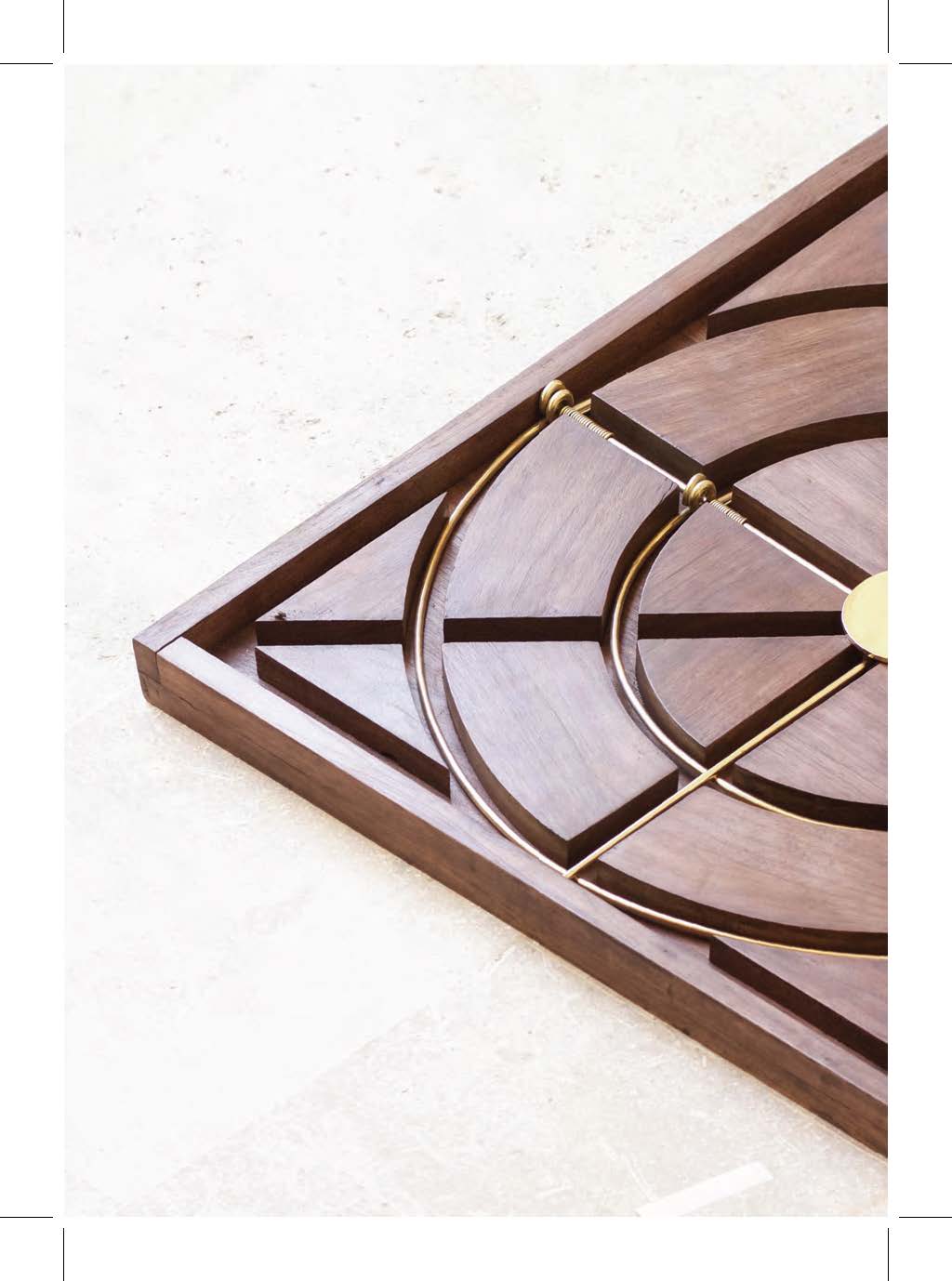

Despite the clearing warning bells, echoes of the axiom-turned-idiom ‘good fences make good neighbours’, can still be heard bellowing. Aaron Bezzina’s ‘Floor Pieces’ are essentially foothold traps displayed in three sizes; a traditional 20 by 20 Maltese tile; a 30 by 30 terrazzo tile, and a contemporary tile measuring 60 by 60. ‘Floor Pieces’ occupy floor space just like a normal tile would, yet with their coiled spring mechanism, they are an ultimate statement in aggressive land demarcation.

The viewers are asked to reconsider their understanding of civic engagement and responsibility; the way we understand ourselves but also our neighbours and our environment. The works are important contributions to the national cultural archive and to what it means to be Maltese. Concurrently, most of the issues that this show grapples with are also global. The artists remind us to reflect upon how we think about what it means to be human, to look in and be conscious of one’s own actions. For when, and perhaps it already has, politics reaches an impasse, aesthetic experiences may still have the potential to impact our thinking.

So for now, while we can, let us stay for a while longer with the poets.

Noticeably, No Ordinary Terrain is missing a curator. The decision to forego one certainly injects more agency and follows the streak of soft positions and explorations that the collective proposes. These positions can be read as playful provocations that nonetheless aim at breaking open certain limitations and function as safeguards, ensuring that institutions hold on to the promise of keeping the museum a fundamental site of the democratic sphere. Undeniably, museums keep wielding considerable power, yet, they are also places where the attitudes, beliefs and values that govern our social relations are shaped, so it is necessary that they remain sites where freedom of expression reigns.

In No Ordinary Terrain, these playful provocations happen on different planes. The collective hired a professional rubble wall builder, Kyle Darmanin, to set up a temporary stone wall structure. A celebration of the much beloved ‘ħajt tas-sejjieħ’, the structure re-proposes the nearly lost art of rubble wall building. At the same time it introduces an actual stone wall in the museum courtyard that is usually not utilised for exhibitions. The tradition rubble wall comes with its own moist, ecosystem in which different plants, reptiles, and insects can thrive but which could potentially wreak havoc on the heavily controlled museum environment.

Propped up on the rubble wall are three metallic discs, which are partially obstructing views of the fountain in the courtyard. The discs resemble oil drums which used to be placed on rubble walls in the Maltese countryside and were meant to keep out ‘trespassers’.

The exhibition regularly tests the borders between the private and the public by taking over non-utilised museum spaces such as the MUŻA corridors, the courtyard but also the community space. Certain works, such as Sandra Zaffarese’s ‘All is not lost’ playfully highlight this takeover. The mound of confetti installed in the corridor poses a dilemma for the museum caretakers who are regularly instructed to keep away from the artworks but who at the same time are also tasked with the corridor upkeep. “All is not lost’ recalls the celebratory gesture of throwing confetti during village feasts, yet it also comes with a gentle reminder about gradual loss and the erosion brought about by the inevitable passage of time.

Another section of the corridor is also taken up by Keit Bonnici’s ‘Dancer’,an intervention made up of a docked robot, which when activated moves amongst the viewers in the corridor. The robot, donning a reflexive vest, can be activated from Keit’s phone when he is not on the museum ground. It offers a reflection on the occupation of space and how it is occupied, both through presence and absence.

Movement is inherently present and facilitated by the exhibition setup. The exhibition progresses circularly, from the corridors to the courtyard and back into the community space, flowing through the less utilised spaces, such as the courtyard and the corridor and freeing up valuable museum space, inviting the viewer to make use of it.

The title, No Ordinary Terrain seems to be a veiled invitation. It instils in the viewer a desire to look at this familiar terrain and also be able to grasp its non-ordinary features. So there is an invitation to look differently at the things around us or, rather to look more closely at our surroundings. Looking becomes an active act - one that requires presence and purpose. Through a renewed way of looking, surroundings which tend to become transparent in their prevalence, can become perceptible again. Comparably, seemingly closed, polarised positions can finally start to be unpacked.

Tom Van Malderen’s ‘Too Illegal to stay, too peculiar to take away’, sits somewhere on this territory. ‘Too Illegal to stay, too peculiar to take away’ is a sculpture that combines elements borrowed from Maltese boathouses and others from traditional local hunting huts. Boathouses and hunting huts share certain characteristics; both possess aesthetically dubious features and are in blatant breach of the law. Yet, one cannot deny that they still form part of the local landscape and the illegality of an act doesn’t mean that they cannot enter our collective consciousness.

Our understanding of ourselves in relation to the other, especially when we are dealing with national identity is determined by a process that we are all participating in. Edward Said speaks of the cultural archive, a collective store that retains sayings, stories but also other types of knowledge that we make use of and that can be used as a measure of our existence in the world. This repository is internalised by the very same people who construct it but it is then externalised through policies, laws, or popular culture.

How entrenched is this repository in our lives? Charlie Cauchi and Tom Van Malderen’s ‘Bigilla’ is a work that questions both artists’ identity and roots in Malta, the island they both immigrated to some years ago. It is a work that questions the artists’ place in country increasingly riddled by rampant racism. Sandra Zaffarese’s ‘A world of their own’ is a delicate drawing installation made up of only paper and ink. The work changes over time, growing and rooting like a lichen infestation. Lichens are healthy colonisers, so just like pen and paper they share a ‘mutualist relationship’. Roots come up again in Keit Bonnici’s ‘Round plant pots do not fit’. It plays with the notion of roots, creating a work that speculates on the existence of plants which, despite unfavourable circumstances, thrive, finding their way through cracks amidst the urban sprawl. The artist presents us an instance where rooting down has a favourable outcome, yet the notion of being rooted, of setting down roots, is often commensurate with situations leading to territorial issues and aggression. Édouard Glissant’s rhizomatic practice in his Poetics of Relations favours an enmeshed root system with no predatory rootstock taking over permanently.

Installed in the community space, one encounters 'Wall on Walls’, where the viewers are invited to express and leave their own personal reflections about walls. These expressions take the form of brief textual statements. The outcomes differ but a rather high percentage express concern at the increasing presence of walls in our lives and at how they are being used as powerful segregational tools aimed at impacting our freedom of movement.

Seared into our mind we have the image of Alan Kurdi, the Kurdish-Syrian boy who passed away on September 2, 2015 during his family’s voyage from Syria, where their Kurdish-majority city had been taken over by ISIL. The photo, quickly becoming a symbol of a geopolitical moment was picked up by major news outlets around the world becoming a point of reflection on a series of grave failures that had ultimately led to the tragedy.

“Freedom of movement” describes the right of a person to travel within a country, or to leave that country and later return to it. It was adopted by the United Nations in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and can be applied to those who are jailed within their own nation or who seek to travel abroad, whether as a refugee, immigrant, or tourist. The term rose to prominence during the recent refugee crisis, when the world first became subsumed by a seemingly endless flow of stories about migration. Every day, we learned about the journeys undertaken by refugees and the nations that welcomed them, or those who sought to stem their influx.

Despite the clearing warning bells, echoes of the axiom-turned-idiom ‘good fences make good neighbours’, can still be heard bellowing. Aaron Bezzina’s ‘Floor Pieces’ are essentially foothold traps displayed in three sizes; a traditional 20 by 20 Maltese tile; a 30 by 30 terrazzo tile, and a contemporary tile measuring 60 by 60. ‘Floor Pieces’ occupy floor space just like a normal tile would, yet with their coiled spring mechanism, they are an ultimate statement in aggressive land demarcation.

The viewers are asked to reconsider their understanding of civic engagement and responsibility; the way we understand ourselves but also our neighbours and our environment. The works are important contributions to the national cultural archive and to what it means to be Maltese. Concurrently, most of the issues that this show grapples with are also global. The artists remind us to reflect upon how we think about what it means to be human, to look in and be conscious of one’s own actions. For when, and perhaps it already has, politics reaches an impasse, aesthetic experiences may still have the potential to impact our thinking.

So for now, while we can, let us stay for a while longer with the poets.

exhibited works: Too Illegal to stay, too peculiar to take away / Bigilla (with Charlie Cauchi) / Wall on Walls / Ħajt tas-sejjieħ (showpiece)

photo credits: Martina Farrugia & Tom Van Malderen